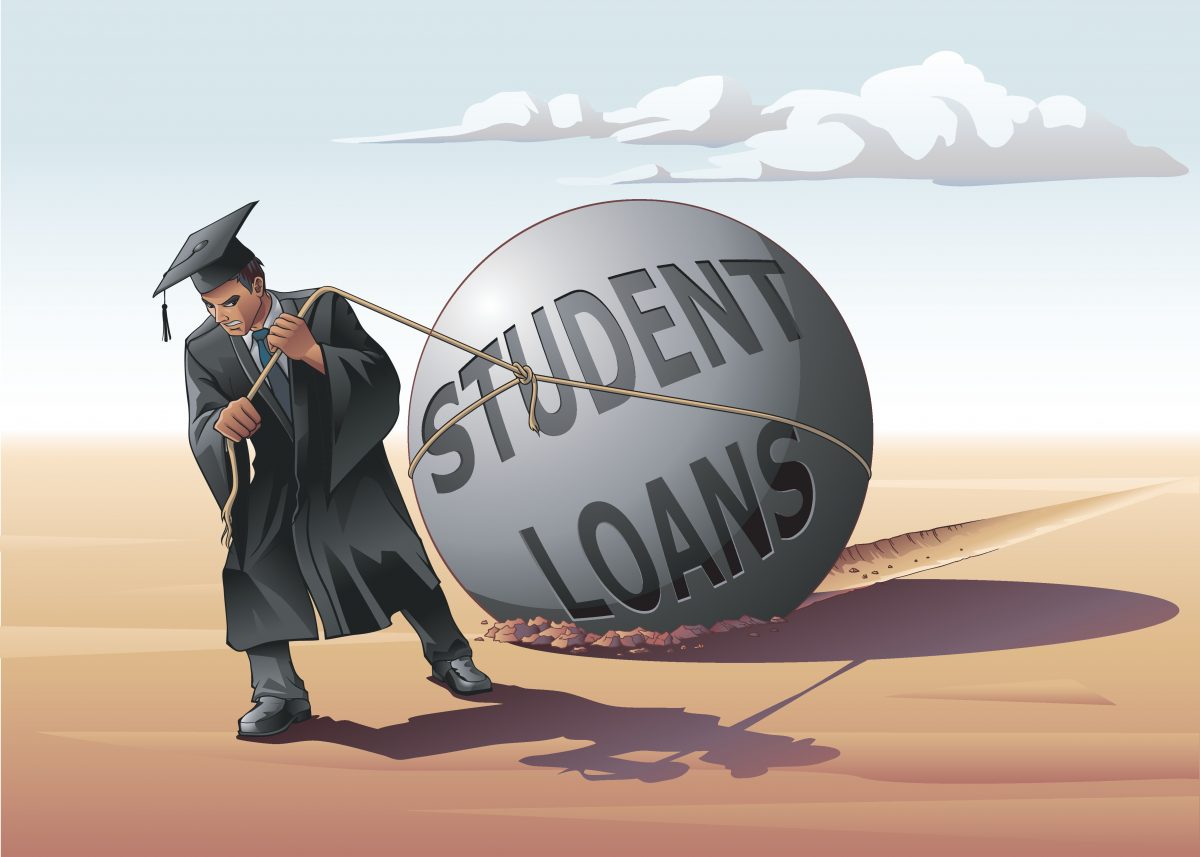

In 2021, the rate of inflation was 7% in the United States, the highest it’s been in over 40 years. Inflation is defined by Investopedia as a measure of how quickly prices are increasing over time. It can occur in the cost of production or the cost of consumption, but when one side experiences a change, it inevitably leads to an equal change in the other side.

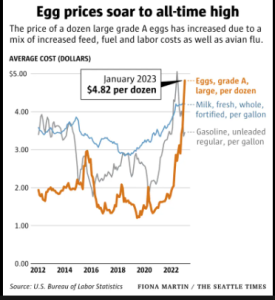

The 2021 inflation was caused by the unique challenges brought on by the COVID-19 outbreak, including supply chain breakdowns, halted workforces and a general loss of disposable income. Due to this, consumer prices were also inflated significantly, leading to many basic items becoming far more expensive than they were in prior years. As the pandemic’s effects abated, the inflation rate fell back to about 3.4% as of 2023. However, consumer prices remain at an all time high, with something as small as a carton of eggs having experienced almost a 70% increase in price.

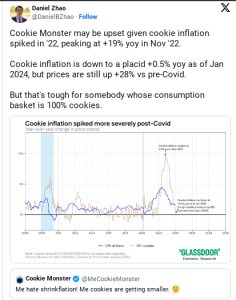

Inflation has been the topic of extensive discussion for decades, and it is perhaps one of the most well known economical phenomena, leading to people being hyper aware of prices. When a product charges more than what it cost previously, it is noticed almost instantly. Despite this, companies still have to maintain a certain profit margin, even in difficult times; and that is where shrinkflation comes in.

Shrinkflation is a term coined by economist Pippa Malmgren, meaning the decrease in the size or quantity of a product that is still sold at the original price as the previous size was (and in some cases, even higher.) Also known as package downsizing, this method is much more subtle than simply raising the price tag, as any changes in portions or sizes are conveniently hidden in the fine print.

Some examples of sneaky shrinkflation in common products across the US include when:

- Gatorade went from 32 oz to 28 oz per bottle.

- General Mills shrunk its “family size” boxes from 19.3 ounces to 18.1 ounces.

- Charmin’ Super Mega Ultra Soft toilet paper rolls went from 366 to 336 sheets.

- Tropicana Orange Juice went 64 to 59 fluid ounces.

- Folgers coffee went from 51 ounces of coffee grinds to 43.5 ounces of coffee.

- Ivory Dish Soap went from 30 ounces to 24 ounces per bottle.

When a company’s scaled back products are noticed, they cite a variety of reasons for the change. Some, like General Mills and Domino’s, blame it on supply chain issues, for example, an increase in the price of raw materials.

Others are a little more creative in their responses, re-branding the reduction as an upgrade whether it’s to help the environment, offer consumers more choice or improve the quality of their products.

For instance, when questioned about the differences in their products, Charmin’ hinted at some new “innovation” that made their new toilet paper squares more efficient, while Folgers alleged that due to some new technology, they had found a way to make the coffee beans lighter so as to still produce the same amount of cups per container.

Gatorade opted to go a different way, touting a new redesign that was supposedly more aerodynamic and easier to grab, claiming that it was a choice that was in the works for a while and had nothing to do with the economy.

According to a study done by Harvard, the first recorded instance of shrinkflation was in 1988 when Chock Full o’Nuts cut its one-pound coffee canister to 13 ounces, and soon other brands followed suit, making it the new standard for the time.

Shrinkflation has been going on for decades, but it is only now that it is getting flagged as an issue, especially since a lot of companies are not upfront about their downsizing, instead just sending it out to the shelves, sometimes in a flashy new look, waiting to be discovered by an eagle-eyed consumer.

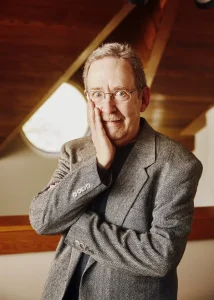

For many companies, this eagle-eyed consumer is Edgar Dworsky (also known as Mr. Consumer.) Dworsky, 73, runs a website called Consumer World, along with a companion website, Mouseprint, for “exposing the strings and catches buried in the fine print.” On these sites, Dworsky documents instances of shrinkflation as well as informs consumers about loopholes in marketing and ways to save money, operating on his own experiences as well as readers’ tips.

As a former Massachusetts Assistant Attorney General in consumer protection, Dworsky has authored a number of consumer protection laws as well, and is shown to practice what he preaches, implementing strategies such as buying in bulk when rates are good so that he’s well protected against having to pay increased prices in the future.

At the time of the profile done by his own website, Consumer World, sources alleged Dworsky had 44 sticks of deodorant, 32 bags of Nestle’s Morsels, 26 bags of chocolate sandwich cookies, 62 jars of barbecue sauce and still more stored items in his house just in case.

Whenever Dworsky goes out, he’s on the hunt for mis-marked products, discounts that are advertised yet not applied at the checkout (in one instance, Dworsky recalls that he and a friend were once able to get away with over $150 of free merchandise thanks to his observations) and instances of shrinkflation.

Another instance of skimpflation is ice cream that is, well, not really ice cream anymore. Ice cream has been a victim of shrinkflation in the past, as the original 56 oz tub of ice cream gave way to the new industry standard of 48 oz, but Dworsky’s website shows that it has also been hit by a little bit of skimping. Many popular ice cream brands such as Breyer’s and Blue Bunny have curiously changed their description from ice cream to instead being a ‘frozen dairy dessert.’

Other examples of skimpflation could include services at hotels or restaurants becoming poorer, with longer wait times or less frequent housekeeping. These tactics are often utilized by companies as they tend to go unnoticed by the majority of the populace, as long as the change happens slowly enough.

As Dworsky notes, “Consumers tend to be price conscious. But they’re not net-weight conscious. They can tell instantly if they’re used to paying $2.99 for a carton of orange juice and that goes up to $3.19. But if the orange juice container goes from 64 ounces to 59 ounces, they’re probably not going to notice.”

Of course, skimpflation is also very difficult to notice, Dworsky adds. “Two scoops of raisins in Raisin Bran — well, how big is the scoop?” In actuality, despite the myriad of causes cited by corporations to justify cutbacks in product quantity/quality it still just boils down to the same thing: inflation.

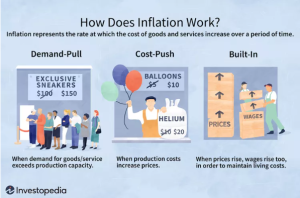

As mentioned in the beginning, inflation is a rise in the general ‘basket of goods’ (commonly purchased products and services,) and all the other ‘-flations’ are just a more innovative way to charge more for the same unit of product or for the same service. So what causes inflation? According to Investopedia, inflation can generally be categorized as being due to three causes: demand-pull inflation, cost-push inflation and built-in inflation.

The COVID-19 inflation can be most accurately designated as a cost push inflation, as rises in the costs of production, i.e. ingredients, packaging and labor, pushed up the costs of consumption. While the worst of this higher period of inflation seems to have passed, the persistence of high prices in the consumer markets seem to remind everyone not to rest on their laurels just yet.

The lion’s share of the responsibility of curbing practices such as shrinkflation does fall to the higher powers, such as the government and central banks. In fact, there was an act drafted in March 2024 titled the ‘Shrinkflation Prevention Act,’ done in an effort to address that issue by making unreasonable price increases or package decreases illegal, spearheaded by U.S Senator Robert Patrick Casey Jr. of Pennsylvania, who has been releasing frequent studies about the current state of the economy, including a series on “Greedflation,” which goes more into the details.

It still remains to be seen whether this act will be passed and help regulate the deception of shrinkflation. In the meantime, there are a few ways that the individual consumer can avoid spending more money on a product than it’s worth. One option is simply reducing the purchase of packaged foods. As Dworsky says, you can shrink a bag of chips, but you can’t shrink a bag of apples. Other tips he provides are:

- Look for the product’s net weight: the weight of the product minus all the packaging

- Use the unit pricing listed on store shelves, as this way you can compare the price per unit of similar products to shop around for which brand offers the most for your money

- Stick with store brands or private label brands. While these brands do undergo shrinkflation the same as name brands, they tend to “lag behind” other brands, meaning that over a longer stretch of time, they are still likely the more cost-effective option

As Dworsky remarks, “…there’s a little bit of Edgar in everyone. How much you admit to, and how much you practice, is another matter.” As we all go out into the world (and especially into our grocery stores,) think to yourself, how can I be more like Edgar Dworsky?

Sources: www.nytimes.com, www.cnet.com, www.ft.com, www.businessinsider.com, www.consumerworld.org, www.npr.org, www.ingredientinspector.org, www.mouseprint.org, money.howstuffworks.com, www.cnbc.com, www.usatoday.com, www.cnbc.com, www.nbcboston.com