In 2023, 21 US species were declared extinct by the US Fish and Wildlife Service. Eight of those 21 species were Hawaiian bird species, and eight were freshwater mussels from southeast America. Extinction has been quite an urgent issue in the world for a long time and this last year just solidifies that it is not only still a prevalent issue, but that it is in fact becoming worse.

Extinction is caused by a variety of factors such as the ongoing climate crisis, the loss and destruction of habitats, the exploitation of these species by humans, and invasive species that have been introduced. These factors all come together to pose a mourning threat to over 2 million species globally. According to a report by the UN, the current rate of extinction is “at least tens to hundreds of times higher” than the rate at which extinctions have occurred over the past 10 million years. In fact, not only have species been going extinct at a rapidly increasing rate in past years, but this might even be building to something bigger.

Angela Calasso, a biology teacher at Becton as well as the advisor for the Environmental Club, suggests that we may be close to experiencing a mass extinction. She defines mass extinction as, “being relative to the amount of biodiversity loss’” and adds that it could be caused by even “25% loss or 50% loss of total species, meaning that while humans themselves may not go extinct, many of the organisms that we depend on for survival could, which would still ultimately disrupt our ecosystem.”

The climate crisis and rising temperatures all around the world have already disrupted many organisms’ ecosystems, as they exacerbate the risk of drought and wildfires, which may cause species that are teetering on the brink of extinction to be wiped out completely. Just this year, a devastating fire struck Lahaina, Maui, which not only caused a lot of damage to property and human lives, but also destroyed many species’ habitats, and even came within 150 feet of engulfing a conservatory for rare birds, including the ‘Akikiki, which is “considered to be the most endangered bird in the US.” Already, island birds are highly vulnerable to extinction, as they often exist nowhere else but in their native land. As mentioned before, Hawaii was hit particularly hard last year, as many of the native birds were wiped out. One bird in particular, the Kauaʻi ʻōʻō was a songbird. This bird and its cousins on Oahu and Molokaʻi were known for having very grand and flashy tail feathers that were once used to make capes and cloaks for Hawaiian royalty.

The disappearance of the Kauaʻi ʻōʻō marks the extinction of the last bird from ōʻō genus within the Mohoidae family, making it the only complete loss of an entire avian family in modern times. Jim Jacobi, biologist with the Pacific Island Ecosystems Research Center, was one of the last people to ever hear the ‘flute-like’ song of this vibrant bird in 1984. He states, “I still get goosebumps – the hair in the back of my neck stands up when I think about it.”

The most effective species recovery efforts come from the Endangered Species Act of 1973, which is meant to create a framework to raise funds and execute plans to defend endangered species and their habitats both domestically and abroad. The ESA has proved successful in saving species from extinction before, for example, the bald eagle. That being said, the Endangered Species Act, while being one of the best options to protect a threatened species, has multiple problems.

One major problem is that species go through extensive research and studies before the decision is made to put them on the endangered species list. However, according to Curry, this process may end up taking too long. Curry says that the species that were declared extinct this year had been listed under the ESA too late. For example, the flat pigtoe mussel, declared extinct in 2023, only went on the list in 1987 which was seven years after it was last seen in the wild, and more than a decade after construction began on the Tennessee-Tombigbee Waterway, a project that experts had concluded would jeopardize its population.

The other major demerit to the Endangered Species Act is that even when a species is on the list, funding disparities run rampant. During a 2016 study by the Center for Biological Diversity, it was found that Congress only provides about 3.5% of the funding that the Fish and Wildlife Service’s own scientists estimate is needed to recover species. In addition to that, the funds allocated to particular rescue plans tend to be biased by political pressures as well as what gets more attention.

According to an analysis by the Associated Press, plants such as the scrub lupine, a flowering plant that has lost native Floridian habitat due to theme parks, drew only 2% of the overall $1.2 billion funds even though more than half of the overall species on the endangered list are plant species. However, plants have had a long history of being left behind in favor of more charming animals. In fact, according to the Congressional Record and Faith Campbell, a longtime environmental advocate, when the Endangered Species Act was first passed in 1973, the entire plant kingdom was nearly completely excluded from the landmark conservation law. They were only added back at the last minute due to a sudden push by botanists from the Smithsonian Institution and Lee Talbot, a senior White House scientist from the Council on Environment Quality.

Efforts to redirect some funds from species that are getting more than necessary have received some push-back. Leah Gerber, a professor of conservation science at Arizona State University says, “For a tiny fraction of the budget going to spotted owls, we could save whole species of cacti that are less charismatic but have an order of magnitude smaller budget.”

As said by the Fish and Wildlife Service Director Martha Williams in an interview, “Each of these species are part of this larger web of life. They’re all important.” So what is our part in all of this? How can ordinary people do something about our biodiversity crisis? People can help endangered species where they live. The pressures of public attention have been shown to make a difference before. Therefore, some conservationists suggest putting pressure on cities or local governments to protect dwindling species. In general, the idea is to inform people about the species that are struggling and not receiving the help they need.

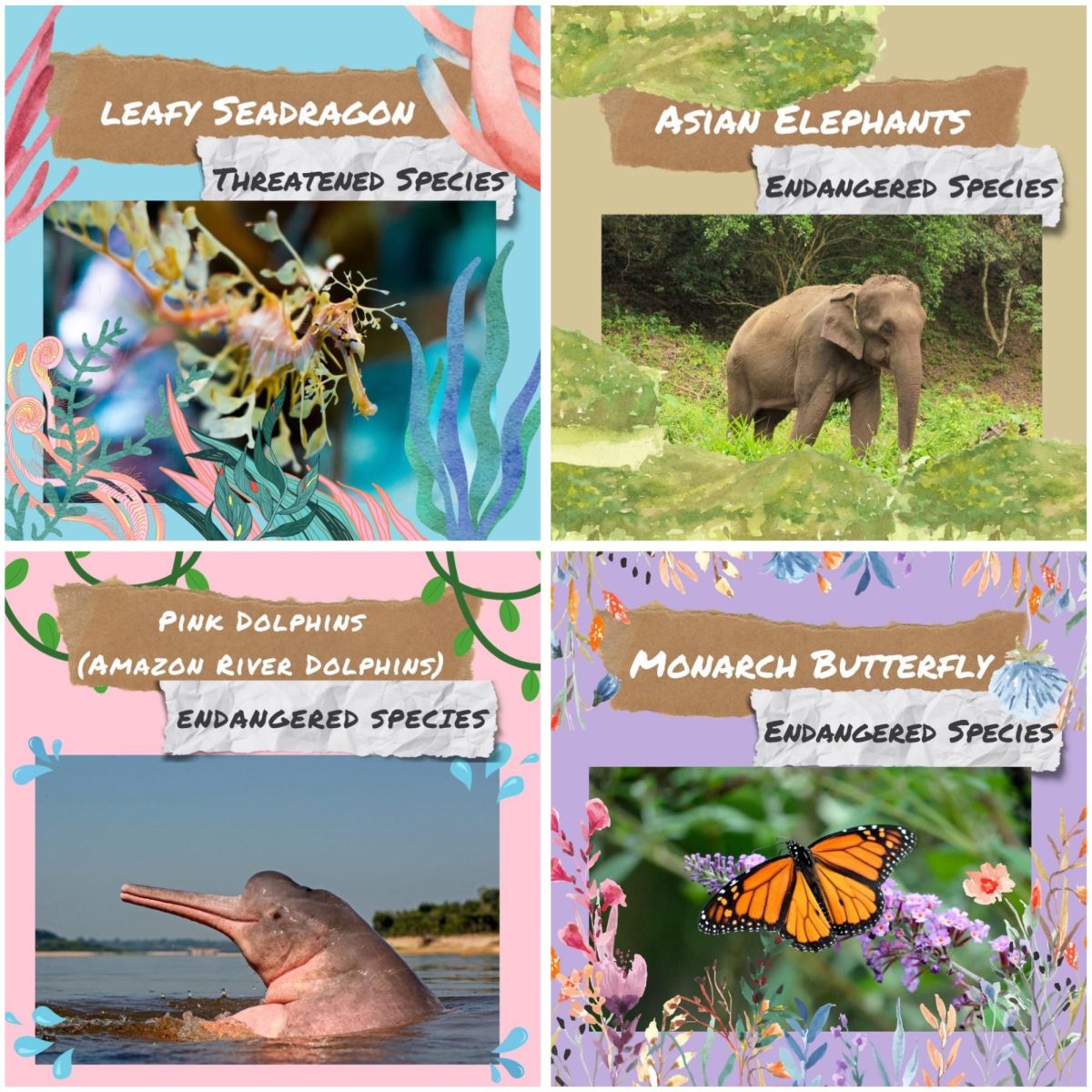

The Becton Environmental Club already does a sizeable amount for this cause with their Creature Feature Fridays and their Endangered Species of the Month. Some other ways to help are to volunteer at a local nature center or wildlife refuge, such as the nearby Meadowland Environmental Center that the Environmental Club has partnered with. Another way is to donate money to your local wildlife conservation funds. As said by Sea McKeon, a biologist, and director of the Marine Program at the American Bird Conservancy, “Your voice is loudest when heard through your dollar.”

One thing is clear: Extinction is a complex and multifaceted issue, but it is urgent and it is happening now, so it requires a swift but well-thought-out and equally complex reaction before it’s too late. A major UN report made in 2019 reported that 25% percent of species in the plant and animal groups are vulnerable to extinction. As stated before by our very own Ms. Calasso, if these species succumb to the many threats facing them, that would be enough to officially declare this as the sixth mass extinction in the history of the planet.

Stay informed and keep up with Becton’s Environmental Club Creature Feature Fridays and their Endangered Species of the Month on social media: on X HERE and on Instagram HERE.

Sources:

https://sea.mashable.com/environment/29728/these-animals-went-extinct-in-2023

https://news.un.org/en/story/2019/05/1037941

https://www.foxnews.com/us/lesser-known-endangered-species-us-threatened-funding-disparities

https://www.statista.com/statistics/204735/endangered-wildlife-and-plant-species-in-the-us/